Back to yesterday ...

In those early years, Mel and I worked out a coping strategy that allowed for him to be free enough to hold down his job as playground director at San Pablo Park during the day -- where he'd follow in the footsteps of Red, his old athletic mentor. He worked on the swing shift at the shipyards as a "trainee" and spent weekends playing quarterback for the Oakland Giants, and -- eventually -- for the Honolulu Warriors of the Pacific Coast Football league that pre-dated the NFL-AFL (Raiders/Niners). He was just about ten years too early, but was headlining the sports pages regularly.

I was the stay at home wife and mother -- who worked long hours in our little music store. Don't remember resenting the arrangement since I was fulfilling "woman's role" as it was expected in those days, making life possible for my husband. It was what we did. Funny, I thought of it as his business at the time, and saw myself in a supporting role, never one of equality.

Rick spent his early years in a playpen next to the cash box and record racks and eventually became adept at working the turntable and making change. When he was about five I became pregnant for the first time with Bobby arriving on time and beautiful! It had been a long wait after years of hoping for such a miracle. Started to immediately plan for my next delivery -- David followed less than three years later. Now it was time to do some major planning for the next phase in our marriage. It was time to build that dream house and get on with the business of mothering.

The demands of parenting began to make necessary Mel's cutting back and taking over the reins of his store while I began to pour over House Beautiful and Sunset Magazines, to think about floor plans and building materials, and to consider hiring the architect and interior decorator to do the preliminary designs.

Around this time Mel's father had retired from Wonder Bread Bakeries, Inc., and his parents had purchased an acre in Danville where he could keep a horse or two and create a truck garden as he'd always dreamed. They had a recently-built attractive one-floor ranch home out in the great open spaces of the Diablo Valley. We'd grown to see this as the perfect setting in which to raise our own growing family. Visiting them meant driving past miles of open land and thinly-developed suburban countryside. Each Sunday was dream-time, and after many months, we found just the spot we would buy, a half-acre bordered by a major creek, with about five sturdy old oaks and many fruit trees. It also had an old abandoned swimming pool (quite large) in the center. This was the final deciding factor for Mel. I recall having misgivings at the time about just how I could live with a pool and two-and-a-third children to keep up with, but this was not negotiable for Mel. This was his land.

What we hadn't counted on was the fact that -- in the real estate world -- by tacit agreement, a "string" had been dropped around those areas of the city where blacks were going to be allowed to live. It was pretty much limited to where blacks were already living. That meant that -- though we had business accounts in both Wells Fargo and the Bank of America -- neither bank would grant us a home loan to make the purchase of the site in the Diablo Valley. In fact, even in Berkeley, we learned that we could not get loans to buy any property above Grove Street, a main thoroughfare that ran from Oakland to Berkeley. African/Americans could only purchase homes between Grove Street and the Bay, and not above Dwight Way to the north. (If you don't know the area this doesn't make sense, I'm sure). There were no large open sites in the city except in the hill areas where Blacks were not permitted to build. Blacks were consigned to what are now referred to as "The Flat Lands."

How on earth do you account then for a young wife and mother who had taken her cues from House Beautiful and Architectural Digest -- whose dream house could not be constructed anywhere that "Gentlemens Agreements" had decided she could buy? We were financially able to afford our dreams, and those dreams were not unlike those of any other young western couple.

The only way that we could make the purchase of the plot we chose was to get Dorothy Wilson, (white) wife of Oakland's (African-American) Mayor, Lionel Wilson (he was a judge of the Superior Court at that time) to buy it for us. Lionel and Mel played semi-pro baseball together and were longtime friends. Meanwhile, I chose a local (Lafayette) architect, Sewell Smith, who was a highly-principled Quaker and a total stranger to begin to draft plans for our new redwood home on that lovely wooded ground.

Rumors began to fly. Threatening letters began to arrive. The architect was challenged. I'm assuming that our Berkeley address had been given out by the permitting offices at the county seat. As soon as the lumber trucks began to deliver stacks of boards for framing, the real threats began to come. "We'll burn every goddamned piece of wood you bring here. Beware!" It was terrifying... .

My (builder) Dad acted as contractor while Mel and several hired workers handled the construction. Having third-grader Rick and not yet 3 year-old Bobby to deal with and David on the way pretty well limited my participation except for monitoring progress. The house was being constructed over late spring and early summer. The weather was extremely hot with many days over 100 degrees. that meant that I usually drove out to the site in the early evenings -- before sundown -- to see how things were going. For the first few months one would have thought that no one lived on the block. I was aware of unseen eyes behind curtains up and down the road, but only interacted with an occasional curious child.

Over the six or so months while the four-bedroom lovely home with the large sundeck was shaping up, just before dark, a car would slow on the road -- usually a woman behind the wheel -- would stop and say, "...I'm Mrs. So-and-so. You may find that people around here are not too friendly, but if ever you should need to -- I live just down the road at ...".My very obvious pregnancy must have softened a few hearts over time. Over the months, most had done as much. The hate they were capable of en masse they were obviously incapable of individually. Interesting. In time the furor died away, but the harm had been irrevokably done.

We learned that the local improvement association had been meeting in extended sessions trying to find a way to halt our construction, or to stem the tide of what was obviously the "Invasion of the Black People." After all, the suburbs were at that time undergoing a building boom for the many more successful warworkers who were caught up in "White Flight" from the inner cities -- and here we were bucking the trend. Mel and I were just a couple of Californians with a long history in the area (remember, Mel's family came during the Civil War), who were just as confused and disoriented by the social changes as anyone else and seeking the same kind of lifestyle for our children as they. How dare they! But dare they did.

A local artist whose property bordered ours on the east was the first to approach me shortly after we moved in. David was but a few months old by then. Edith Dinkin and her husband invited us to an occasional gathering in her studio, and occasionally during the day when the kids were napping, we set up our easels creekside and she would give me painting lessons. It was a brave act on her part.

We'd purposely chosen a site in an unincorporated area just outside the city limits where I'd expected to find more individuality and less group-think. The homes were large and small, architect-designed and owner-built as well. There was a converted chicken shack across the road, next door to an attractive ranch house with shake roof and stone patio, etc. There was a Mormon couple with two kids, Al and Bessie Gilbert, who lived on their site in a trailer while they built their new home one board at a time.

The year after we moved in Dr. Harvey Powelson, a psychiatrist with a wife and 5 young kids built a home about a block away. I later learned that the Powelsons had chosen that site precisely because we were there, and would give their kids some "diversity" in their lives and erase some of the homogeneity of the burbs. There were so many opposing dynamics to contend with. It was oppressive to have become "the Negro family" of a resistant neighborhood, in time we all survived.

Over that first year or so my only response had been one of silence. I was troubled and confused, and certainly not used to being rejected on such a scale. I was also alone with the problems. Once the house was completed, Mel had gone back to work in the store and to life in Berkeley. The day-to-day life of adjustments to this highly irrational situation took its toll. I'd said nothing to my family or city friends about what as happening to us since my pride just wouldn't allow it. I had to make this work.

I can recall the day it started to turn around and I found my voice. It was the day that a very high profile attorney, Bob Condon, and his wife (just around the bend in the road and across the creek) Eleanor (the ceramist, decided to hold a dinner for the community. "We can take care of all this anger if they just have a chance to meet you two," says Bob. (Ungrateful!) my response was, "...no one is going to hold a dinner in order to show this community that I'm acceptable. They have every right to not want me here. What they do not have is any control over my being here!" "It is not true that one of their rights is the right to deny me mine!" This was about six months into silently hoping that we wouldn't be burned alive in our beds. "How dare they!" Poor Bob didn't expect this outburst, but was smart enough to see that it was coming straight up from my shoes and after months of unspeakable fear. He was not insulted, but allowed me the pride of defending myself. I could not have the Condons guaranteeing my acceptability. No one had that right or obligation. Along with the Dinkins, the Condons and the Powelsons became my friends and supporters. I owe them much. They befriended me with a sense of equality and not one bit of condescension. It was a brave beginning, and there were many new friendships in the years to follow, some that persist to this day.

More to follow...

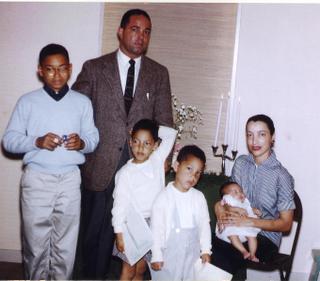

Photo: Taken on the occasion of Dorian Leon Reid's dedication service at the Mt. Diablo Unitarian-Universalist Fellowship in a small bungalow on Pine Street in Walnut Creek, CA.