Thinking about Elliot and Jason Blaine and "The Music People, Inc." ...

Thinking about Elliot and Jason Blaine and "The Music People, Inc." ...Maybe I witnessed the crossroads where Hip Hop Culture and Gangsta Rap came together in the City of Oakland. Maybe.

During those years as the proprietor of Reid's Records, my major music supplier was an Emeryville firm run by a father and son team of former New York entrepreneurs. "The Music People, Inc." was a one-stop operation that specialized in small label releases for Mom & Pop music stores that couldn't afford to buy in the huge quantities common to discount house merchandise orders.

Wholesale costs are based on volume -- and we small stores were buying dozens of an item while the big dealers were ordering caseloads. One of the secrets of the industry was that -- with the feature of return privilege -- those big guys were buying in huge quantities and then returning the unsold items for credit, making the economics of the distributor highly volatile. Failures of record stores were frequent -- leaving Music People with merchandise returns of releases that had lost their shelf life long before and were by then completely worthless.

We paid more at wholesale than the discounters sell their products for over the counter. The only way to survive was to specialize; and that we did -- in black gospel music.

We were a motley group that could only exist day-to-day by the goodwill and patience (that's saying it as kindly as possible) of a family that carried most of us on the books with a perpetual indebtedness that held us in a never-ending grasp of debt and servitude. It was probably a marriage of convenience; as the Blaines needed our little band of intrepid store (mostly young and/or black) owners on their books in order to survive in the wholesale marketplace as a bottomless pool of "receivables" that serves as the coin of the realm in the chaotic music business.

We were brought together from time to time for celebrations - hosted by Elliott and Jason -- that heralded the release of some fledgling recording artist. Over time we enjoyed their largesse but also developed a sense of duty to them. After all, it was Elliott Blaine who allowed me to keep possession of our store when Mel crashed, financially, and lost it all. The wholesale bills I inherited were staggering. Over time it was the willingness of Music People to allow the time for me to recover enough to change the direction of the store -- and to shift seriously into black gospel music at a time before the general market had recognized this as a lucrative field. That made the difference between survival and utter failure. But that was back in the Seventies and -- eventually the disaster was overcome and Reid's survived even Mel's tragic collapse and eventually death in the Eighties, and still does after 62 years of struggle. Another generation of Reid's continues the reign, our youngest son, David, is now at the helm.

Meanwhile, however, I watched Stanley (MC Hammer) emerge along with a string of young rappers who came under the wing (and exploitation) of Jason Blaine. Stan was a nice kid who was known to hang around the A's dugout at the Oakland Coliseum -- to dance like a demon -- and exude enough personality to light up a large room. We knew he would one day blaze a new trail in the record industry, and he did, though his trajectory failed in less time than it takes to tell the story. I'm sure that the Blaines were instrumental in his ascendance.

They eventually shifted their inventory to take advantage of the new wave of Gangsta Rap that was emerging in Oakland, and their One-Stop operation slowly lost its value to me and my "old fashioned" inventory needs. The son, Jason, became an ardent promoter and, eventually, a producer of rap artists and I watched as the wave of the genre began to sweep like wildfire through inner cities across the country, giving status and bling to a new generation of unlikely baggy pants black-hooded finger-jabbing stage-stalking stars with little to share save unbelievable energy and a formidable beat! But I'm quick to add that a number of true poets rose among them, and continues to do so.

Early on, I found myself caught in a strong resistance to the kinds of material coming out of the industry. It was strange to have young elementary school children come into the store with their little walkman tape players in hand -- to buy cassettes that played the questionable material of LLCoolJ directly into their ears. I'd listened to those tapes and knew that -- if it had been a record they'd purchased and placed it on their family's player for all to hear, their parents (most of whom I knew) would have been shocked and horrified! Instead, I'd watch them walk out of my store (having split the plastic, hurriedly inserted the tape, and checked the earpiece) with an evil grin on their little faces -- knowing that I'd supplied them with sounds and language and mayhem and no one else (but their young friends) would know. I could hear them at times, gathering on the street corner rapping a word-for-word replication of things far beyond their experience and it saddened me. And -- I'd become an unwitting co-conspirator by simply making an honest sale. I couldn't do it.

I posted a sign in my window to the effect that those releases would not be available at Reid's and that I'd suggest that they pick them up across town at Leopold's. Music People, Inc., was extremely unhappy with me, and my quiet protest caused a small riot in the daily newspapers when a reporter happened to drive past and made note of my sign. The radio stations picked it up as well. I was suddenly a minor celebrity after a radio talk show host stopped by for an interview that was aired throughout the area.

"Have you not, in effect, denied the right of free speech by such an action?"

"Nope. Everybody's rights were honored. The record producer had the right to make the record. The artist's right to perform the material was respected. The child has a right to buy it if he or she so wishes. But I have a right not to stock it if that is my wish. Every time time I purchase records for resale, I'm making a pre-selection for my customers. There is nothing special in this action. I chose not to sell a product for my own reasons. That is my right."

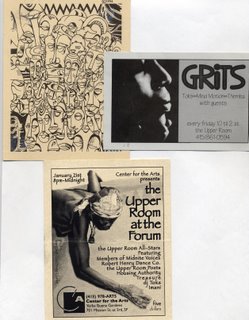

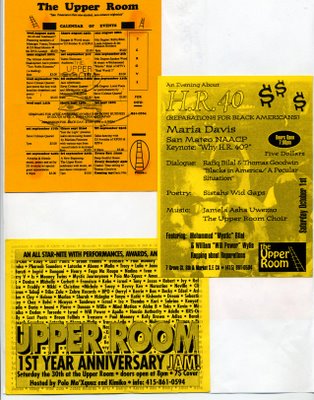

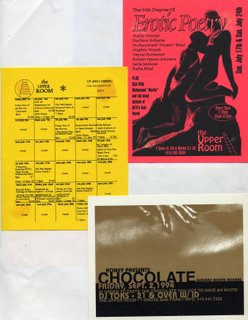

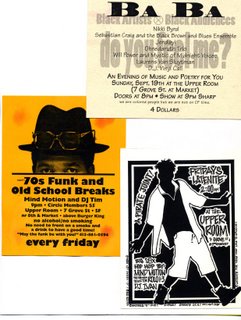

Over the ensuing years -- watching the tragic deaths of artists like Tupac Shakur (a true Hip Hop poet), Biggie Smalls, et al, I've seen nothing that would have caused me to regret that action. I saw Music People, Inc. and the record industry in general elevate and commercially exploit the genre to a place where materialism in the form of gilded teeth and diamond encrusted Rolexes and multiple stretch Hummers overpowered the arts movement as represented by the Nu Upper Room artists and the exciting non-abusive arts they expressed so magnificently.

I see the remnants still in Jill Scott, yes, and Will Power et al. Maybe their time has come -- and the wisdom of Bill Moyers will finally bring them the recognition in American Letters they so richly deserve.

With the experience of the Nu Upper Room so fresh, I could not be satisfied with what was beginning to evolve as a distortion of Hip Hop, or, at least a distant piece of the whole that was to form the basis of new black music -- as the direct results of commercial exploitation by a heartless industry. This would become the commercial face of this new art form, and would eventually crowd out the Hip Hop culture that I'd come to so admire.

Anybody wanna fight? (Grin)

Photo: Wish I could find some way to donate these historic flyers of a brief era in Camelot to a place that would treasure them as I do. Any ideas? There are more ... .