Revelations ... and a re-examination of a nation's twisted psyche ...

A very dear member of my family left the earth at the end of the day on the 4th of July. This was one of the dearest women I knew. The world is a poorer place without Marionella LeBeouf Cobette (an Allen-Breaux descendant).

As is more and more true in these final years, her death was a grim reminder of how much work there is still to be done before my time arrives. As one of the unofficial holders of the family history, it becomes ever so important to try hard to use the time well and to leave a legacy of truth for others to build on in years to come.

Over time I've done fairly well with researching both my maternal and paternal lines and it's all fairly neatly stored in two large binders -- with maps and photographs and artifacts that help to tell the stories.

The lineage has been traced from two who entered the country several centuries ago: My maternal ancestor, Vincent Breaux who left Loudon, France, in 1631 with an early wave of the Acadians who traveled over time to Nova Scotia, then to Maryland, and finally being permitted by the Spanish (who held Louisiana at the time) to settle in St. James Parish, Louisiana. Then there was my father's earliest traceable ancestor, Raimond Charbonnet, who started in Thiers, France, born between 1646-1649 and married to Gabrielle (Dutuel) Charbonnet. For both I've been able to document all the way up to my own parents, Dorson Louis Charbonnet and Lottie Allen Charbonnet. But all roads lead at one point to the slave curtain, 'til now impossible to penetrate.

The French Catholics have kept great records that came alive for me through church documents. There was lots of help from other researchers such as "cousins" Clarence Breaux of Louisiana who provided 26 generations along with Prof. Robert Brault (note German spelling) of Canada with whom he wrote his book on the Breaux family. There was also researcher Ken Jenkins, an architect at Louisiana State University. His wife's family, Charbonnet, intersects with mine far back in New Orleans history. Her line is white. Mine veers off in the early 1800's when there was a liaison between a white Charbonnet and a "Free Person of Color" with whom he had a lifelong relationship that produced eleven children -- one being my great great grandfather, Dorson Louis Charbonnet, Sr.

Ken Jenkins says in a letter:

"The Charbonnet story is such a great one - wish we knew enough to publish. It has the French-Indian War, French Revolution, slave revolt in Santo Domingo, War of 1812, Gone-with-the-wind Plantation, in-marriages with French - Spanish - African American - Canary Island - and American families. It has prisoners of war in Canada and the Civil War - people serving in the Creole Militia - Free People of Color - Old French Family arrogance - lost love, lost chances, lost fortunes ... Judges, Admirals, Street Car Conductors ... and hint of lost French Royalty."

But the above serves only as a prelude to the emotional time I spent yesterday afternoon. In the wake of my cousin's death I decided (finally) to try to break the barrier on slave ancestors. Where were they from? From which African tribes? To whom were they sold? Until her death in her mid-nineties, my mother's sister, Vivian, told stories about her great grandmother, Celestine, whom she remembered well. She was called "Mom" and (according to Vivian) walked along the levee with a long pole (like the herders among the Masai?). I knew that she and her daughter, Leontine, (my great grandmother) spoke only French and rarely wore shoes except on Sundays -- and that Mamma (Leontine) would bring out a tiny pipe from behind the stove every evening after everyone else was in bed in that tiny cabin on the banks of the Mississippi. Little girl Vivian would be allowed to fill it with tobacco and "tamp it down" as an honored privilege. I remember Mamma (Leontine) who lived to be 102 and died when I was 27 years old. (Her story is told on our family web site -- link provided on the left -- under California Black Pioneers.)

Revisited a site I'd not seen for a long time -- AfriGeneas -- a web site created by Vivian King Nelson et al established at the University of Mississippi to provide the tools for African American researchers to trace their ancestry. I'd tried years ago to break through the slave curtain but gave up after a time. They've now added the slave records, narratives, Freedman's Bureau, countless new archives to work through -- to what was already a very rich resource. It was those records that I spent the afternoon going through looking at slave ship manifests for clues to Celestine's early journey. I had little to go on, only the name. Church records at the Catholic Diocese at Baton Rouge had her listed as "Celestine of no last name." I'd always found that fact strangely comforting in that she must have refused to take the name of her owner. But that was only true until her marriage to (Cajun farmer) Eduoard Breaux in 1865, just after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed.

Until yesterday I'd assumed that those ship's cargoes were carrying slaves from Africa but it didn't take long to realize that this was no longer necessarily true. By the years 1800 through 1840 (the period covered in the slave records) slavery had been in effect for over 200 years. The names listed in those manifests were several generations later than the original "cargoes." What was shocking to me when I was able to internalize it -- was that a large percentage of these people were described as mulatto with brief descriptions beside their names (mostly first names, only). They are listed as tawny, yellow, black, brown, light tan, very dark brown and almost white. I was surprised at the ages given, few were over 35 with most in their late teens and early twenties. They were so young. There were many described as suckling mothers. There were also many of children of all ages.

These were not ships unloading their human cargo from across the ocean. This was slave stock being shipped as a part of interstate commerce. They were being transferred as an inheritance from some slaveowner's will to heirs living elsewhere in the South. They were simply property - chattel -- being moved around the colonies and perhaps to and from the Gulf Coast islands.

It was chilling to read on the AfriGeneas website encouraging words about the need to stick with the search despite the difficulties, "...remember that slaves were currency. Follow the money. They'll show up in wills and as capital in estate sales; in bank records. They will be traceable in the family bibles of owners." All true.

But the most shocking of all was the moment when I realized that 200 years out, the reason that there were so many mulattos listed was due to the fact that slave owners used their own sperm to boost their holdings. Is what I was seeing in those records proof that men were literally selling their own children and grandchildren? Is this the ugly secret that's so hard for this nation to face? Could this be the reason that we've not yet recovered completely from the scars of the Civil War? Two hundred years out, there was little reason to continue to import slaves since the nation's slave owners were creating their own slave stock. The utter callousness of such a practice is hard to accept, but if we're to think of slaves as currency, what other conclusion can be drawn? I would urge anyone reading this to visit those web pages and read through those descriptions for yourself. If you draw different conclusions, I would be most interested in hearing from you.

I'd read only recently in a biography on George Washington that he'd often paid his gambling debt with slaves. We're all by now familiar with the schizophrenic writings of Thomas Jefferson on the subject of black inferiority despite the liaison's both his father and he had with Sally Hemmings and her mother.

I didn't find Celestine among those listed in the ship's manifests. Not anyone by that name. Not sure where to go from here. Nor did I find the name of her owner, the Breaux. This may mean that it was not she who was brought through the Middle Passage -- but her parents, or theirs, sometime in the 1600's. As Aunt Vivian described her, she was a mulatto (one white parent). Since she was owned by a family into which she later married, it's unlikely that I will find her on the manifest of any ship.

What a way to spend Independence Day. I came away from the AfriGeneas pages feeling a singular part of it all; a descendant of slaves, slave owners, several veterans of the New Orleans Militia, of a French naval officer who fought in the Haitian Revolution, a white general and an admiral in the Civil War, and related to both the brutal shame of and the ultimate victory over slavery that my family and those like it present to the world. Indeed, "...one nation under God."

And here we are on this Independence Day, seemingly more "under God" than ever and I have absolutely no idea what to do with the obvious paradox, or just how to reconcile our cruel history and our current expressions of brutality with our professed religious beliefs; beliefs for which we are apparently willing to fight, kill, and die, but by which we will not live.

Take the time to visit those slave records and draw your own conclusions. It may be that we're ready to have this conversation, and that some resolution will come in our time.

Hoping that your's was a thoughtful holiday filled with family and friends. Ours was sad with the loss of a dear one, but well spent remembering.

Marionella LeBeouf Cobette

(1925-2005)

(1925-2005)

would have surely wished all "cousins" a blessed and loving day of celebration in her gentle way of loving unconditionally. The country and the world could use more of that.

We will miss her ... .

Photos: Left is a picture taken in 1944 by cousin Janet Duncan -- it's the site of the Allen (Breaux) Cabin in Welcome Post Office, St. James Parish, Louisiana. The cabin had burned down, accidentally some time in the Seventies. Only the land remains.

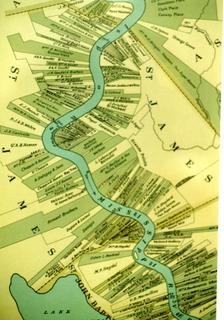

The second is a plantation map showing the Breaux Plantation among others. All front on the river and meet at the levee. Mammá's small site was left to her mother, Celestine, by Eduoard Breaux, her (Cajun) legal husband and the plantation owner. Mammá lived in that little house until her death in 1948, surrounded by her brood of children, grandchildren.